Toxic Coloniality or Colonial Toxicity?

- Date

- 24 March 2023

- Time

- 17:00 -18:45

Samia Henni is a historian and an exhibition maker of the built, destroyed, and imagined environments. She is the author of the multi-award-winning Architecture of Counterrevolution: The French Army in Northern Algeria (gta Verlag, 2017, EN; Editions B42, 2019, FR), the editor of War Zones, gta papers no. 2 (gta Verlag, 2018), and Deserts Are Not Empty (Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2022). She is also the maker of the exhibitions Archives: Secret-Défense (ifa Gallery, SAVVY Contemporary, Berlin, 2021), Housing Pharmacology / Right to Housing (Manifesta 13, Marseille, 2020) and Discreet Violence: Architecture and the French War in Algeria (Zurich, Rotterdam, Berlin, Johannesburg, Paris, Prague, Ithaca, Philadelphia, Charlottesville, 2017–21). She teaches history of architecture and urban development at Cornell University's College of Architecture, Art and Planning.

Abstract

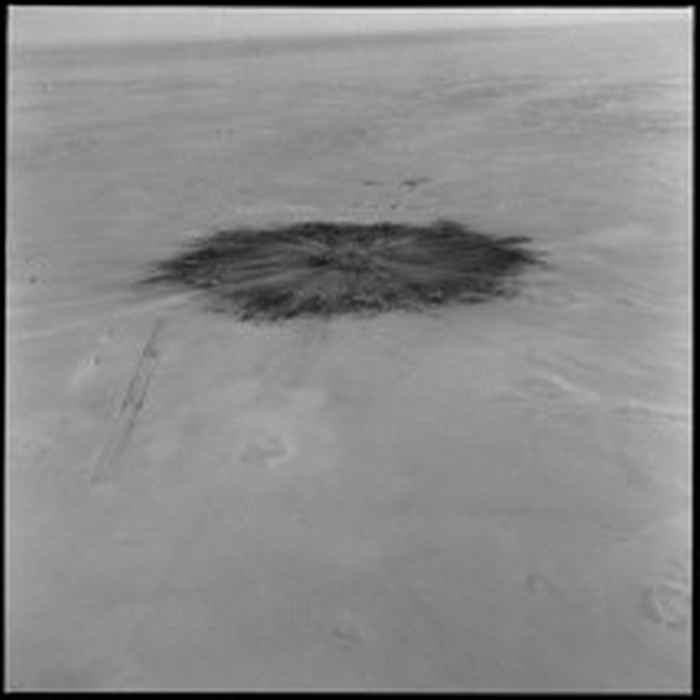

On February 13, 1960, six years after the outbreak of the Algerian Revolution, or the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962), the French colonial authorities denoted their first atomic atmospheric bomb in Reggane in the colonized Algerian Sahara. Codenamed “Gerboise Bleue” (Blue Jerboa), it had a blast capacity of 70 kilotons, about 4 times the strength of Little Boy, the United States’ atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima a month before the end of the Second World War. Blue Jerboa was followed by other atmospheric detonations, as well as various underground nuclear bombs in In Ekker, which continued until 1966, four years after Algeria’s formal independence from France.

To secretly conduct their nuclear weapons program in the colonized Sahara, the French army designed and built two military bases: one in Reggane, in the Tanezrouft Plain, approximately 1,150 kilometers south of Algiers, and another one in in Ekker, in the Hoggar mountains, about 600 kilometers south-eastern of Reggane. The use of the Algerian Sahara as a nuclear firing field spread radioactive fallout across Africa and the Mediterranean, causing irreversible contaminations among human and nonhuman lives, natural, and built environments.

This lecture aims at tracing and naming the spatial, atmospheric, and geological impacts of France’s atomic bombs in the Sahara. It exposes the coloniality and toxicity of the norms and forms of France’s weapons of mass destruction, including the classification of its very sources. It also examines the spatialities and temporalities of France’s colonial toxicity, or toxic coloniality, and explores the lives and afterlives of radioactive debris and nuclear wastes.