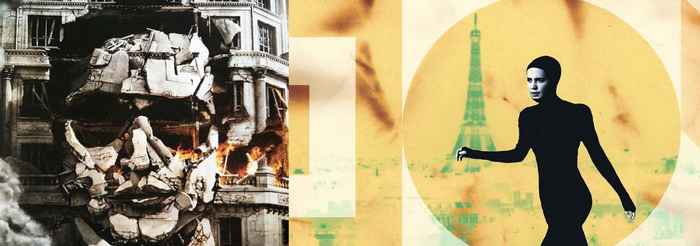

After the Political, Aesthetic Affiliation: On Assayas's Carlos and Irma Vep

- Date

- 2 May 2023

- Time

- 16:00 -18:00

In the three-part mini-series Carlos (2007), Olivier Assayas identifies a peculiar problem for the functioning of terrorism on a global scale. Namely, by succeeding in his free-lance work as a terrorist, at a moment in which

political affiliation has become less determined by autochthonous values than by financial incentives and international renown, Carlos the Jackal’s authority is undone by the visibility he was already famous for seeking in

the media. In other words, by becoming a star, and delighting in his own image, Carlos gives up his agency as a socalled freedom fighter. To appear is thus to lose power, and at the very moment in which he believes himself to be

most in possession of it. Accordingly, what Assayas explores in Carlos, I want to suggest, is the movement from post- political forms of resistance on a global scale, where solidarity is never expressed in uniform, representational

terms, back to a conception of the political in more traditional terms of the friend/enemy dynamic—to a way of regarding unification and collectivity in terms that have become obsolete in the neo-liberal era, even if neoliberalism is what makes the appearance of the friend/enemy relation possible in strictly financial terms. After all, the friend/enemy distinction depends entirely on consistency and unification at the level of appearance itself.

In this talk I will argue that Assayas’s recent television works, Carlos and Irma Vep (2022), simultaneously stage the problem of appearance in uniform terms, and propose, especially in Irma Vep, a way of understanding

political affiliation in necessarily uneven aesthetic terms, where belonging depends less on relations of identity than on the very differences that constitute a need for “relation” in the first place. In doing so, I will explore the ways in which Assayas continues to develop an understanding of aesthetic politics that can be understood as a corrective to Carl Schmitt’s concern, as articulated it in The Concept of the Political (1932), that the political, should it descend to the level of the social, would become indistinguishable from economics, entertainment, and morality.

The point, of course, is not that that politics can or necessarily should be separated from economics, entertainment and morality. Rather, what Assayas’s television work makes especially clear is that the distinction was never entirely operative in the first place, and that any effort to return to it will remain entirely insensitive to less predictable flows

of political affiliation— namely, forms of affiliation that are aesthetically conceived. One consequence of recognizing that the political may never have been distinct from the social, to begin with, is that what we regularly

diagnose as neoliberalism might also describe its opposite: a necessarily uneven mode of collectivity.

Brian Price is Professor of Cinema and Visual Studies at the University of Toronto. He is the author of two books, A Theory of Regret (Duke University Press, 2017) and Neither God nor Master: Robert Bresson and Radical Politics (University of Minnesota Press, 2011). He is also a founding co-editor of the journal, World Picture and series editor for Superimpositions:

Philosophy and the Moving Image (Northwestern University Press).